The Global Silhouette: A History of Intimate Aesthetics

In the quiet privacy of a dressing room or the hushed interior of a doctor’s office, women often carry a silent weight: the question of whether they are "normal." This concern, while intensely personal, is rarely born in a vacuum. It is the byproduct of a century of shifting visual standards, media influence, and a deep-seated human desire to align with an aesthetic ideal.

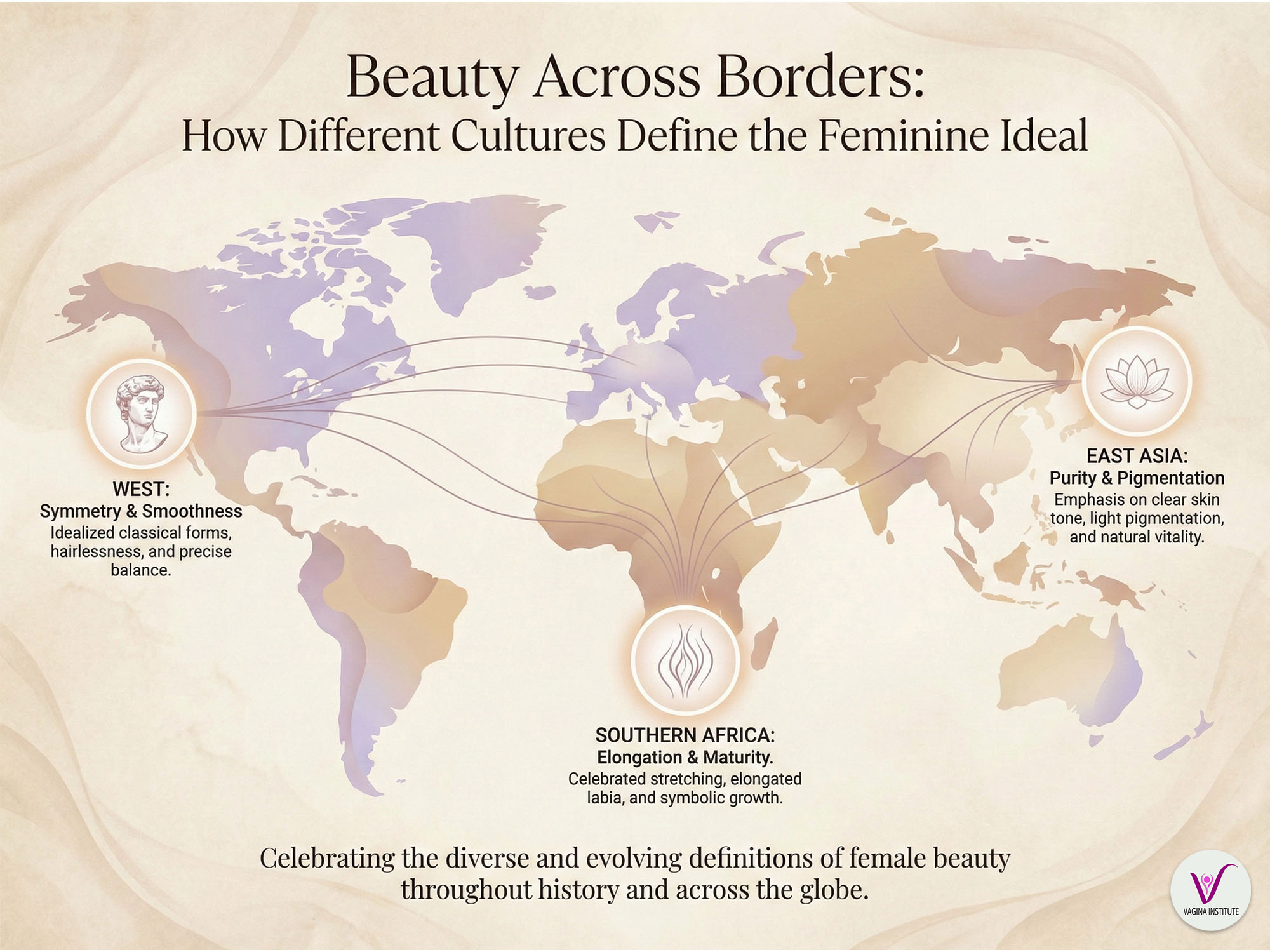

Yet, what we consider the "ideal" today—often characterized by symmetry, hairlessness, and a minimalist profile—is a mere blip on the radar of human history.

When we look at the history of female aesthetics, we see a fascinating interplay between biology and culture. From the ancient plains of Southern Africa to the high-fashion capitals of the West, the definition of a beautiful woman has always extended beyond her face or her waistline. By looking at how different cultures and eras have viewed the female form, we can move toward a more grounded, traditional appreciation of our own bodies, recognizing that "perfection" is not a fixed point, but a wandering star.

The Western Shift: From Nature to the "Barbie" Ideal

For much of Western history, the intimate anatomy of a woman was treated with a mix of clinical detachment and artistic romanticism. If one looks at classical European art—from the marble goddesses of Greece to the lush canvases of the Renaissance—there is a noticeable lack of detail in the pelvic region. Modesty was the prevailing virtue, and the female form was often depicted as smooth, almost ethereal.

However, the late 20th and early 21st centuries brought about a radical shift in how Western women view themselves. The rise of high-definition photography, the ubiquity of adult media, and the trend of total depilation (the removal of all pubic hair) have created a new, somewhat rigid standard. This is often referred to as the "Barbie look"—a desire for small, symmetrical labia minora that do not protrude beyond the labia majora.

This trend has led to a significant increase in labiaplasty, a surgical procedure to trim or reshape the inner lips. While many women seek this for physical comfort, a substantial number do so out of a perceived aesthetic "flaw." In a culture that values clean lines and youthful minimalism, the natural variations of the female body—where one side may be longer than the other, or where the inner lips are naturally prominent—are often unfairly pathologized.

It is important to remember that the Western obsession with a "tucked" look is a relatively new phenomenon. Prior to the 1990s, the natural "bush" and the varied shapes of womanhood were accepted as the biological baseline. The modern push for surgical perfection is less about health and more about a cultural preference for a streamlined silhouette that often ignores the functional reality of a woman's body.

"What one society seeks to 'fix' through surgery, another society painstakingly cultivates as a crown of beauty."

The African Tradition: The Beauty of Elongation

While the West has moved toward a "less is more" philosophy, several African cultures have historically held the opposite view. In various parts of Southern and Eastern Africa, particularly among the Khoisan people and certain Bantu-speaking groups, the elongation of the labia minora has been a celebrated practice for centuries.

In these traditions, long labia—sometimes referred to by early Western explorers as the "Hottentot Apron"—are not viewed as a deformity but as a mark of maturity, fertility, and supreme femininity. In many of these cultures, girls are taught by elder women to perform stretching exercises from a young age. This is often seen as a rite of passage, a way to prepare a woman for marriage and to enhance the pleasure of both the woman and her husband.

For these women, the "Western ideal" of small, hidden lips would be seen as underdeveloped or unattractive. The elongated labia are considered a decorative and functional part of their womanhood, something to be proud of. This cultural practice underscores a profound truth: what one society seeks to "fix" through surgery, another society painstakingly cultivates as a crown of beauty. It challenges the notion that there is a single, biologically "correct" way for a woman to look.

Asian Aesthetics: Purity and Pigmentation

In East Asian cultures, particularly in Japan and Korea, the aesthetic standards for the female body have historically leaned toward a different set of priorities. Here, the emphasis is often on the color and the perceived "purity" of the skin.

Historically, Japanese Shunga (erotic art from the Edo period) depicted the female anatomy with a certain stylized exaggeration, but there was always a focus on the contrast between the pale skin of the body and the pinker tones of the genitalia. In modern times, this has manifested in a booming market for "lightening" creams. Many women in these regions feel a sense of self-consciousness if the skin of the vulva or inner thighs is darker than the rest of their body—a natural occurrence due to hormones and friction that is often misinterpreted as a lack of hygiene or "overuse."

Furthermore, while Western women have moved toward total hair removal, some Asian cultures have traditionally viewed a moderate amount of pubic hair as a sign of vitality and health. However, as Western media globalizes, these traditional views are often in conflict with the new "global" standard of hairlessness, creating a complex tug-of-war between ancestral values and modern trends.

During the Victorian era, some Western doctors actually warned against excessive grooming, believing that natural hair was a necessary biological shield. Standards of "hygiene" are often as much about fashion as they are about health.

The Roman and Greek Influence: The Virtue of Grooming

To understand the roots of Western grooming, we must look back to the classical world. In Ancient Rome and Greece, the "ideal" woman was one who was meticulously groomed. Pubic hair was often viewed as uncivilized or "animalistic." Upper-class Roman women used various methods—from tweezers to primitive depilatory creams made of resins and bat blood—to achieve a smooth look.

Yet, unlike today’s surgical trends, the goal wasn't to change the shape of the anatomy, but rather to showcase the body in its most "civilized" state. The focus was on the skin and the hygiene of the woman, reflecting the broader Greco-Roman values of order and discipline. This historical context shows us that the desire to groom is not a modern vanity, but a long-standing tradition of women managing their bodies to reflect their social standing and personal pride.

The Reality of Symmetry and Variation

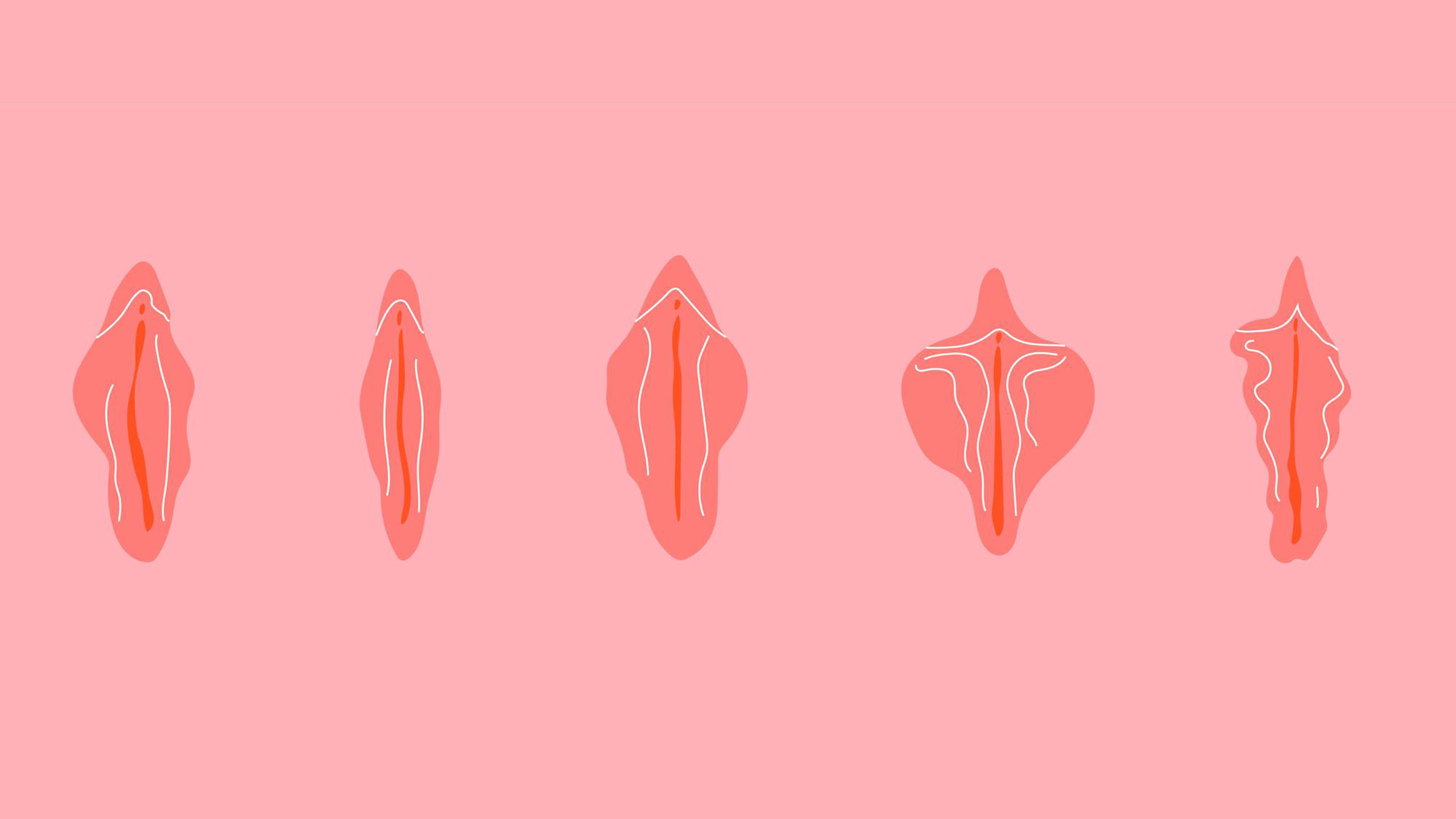

One of the most common anxieties women face today is the lack of symmetry. We are told that "beauty is symmetry," and while that may hold true for the placement of eyes or the shape of a smile, it is rarely the reality of human biology.

The human body is not a mirrored image. One breast is often larger than the other; one foot is slightly bigger; one side of the face has a deeper dimple. The vulva is no different. Natural variation—where one labia is longer, thicker, or a different shape than the other—is the biological norm. In fact, true "perfect" symmetry in the pelvic region is not so common.

When we look at the historical and global landscape, we see that women have survived and thrived with every possible variation of shape and size. The "perfect" look that is currently popularized in the West is an outlier in the grand history of femininity. It is a specific aesthetic choice, much like the "beehive" hair of the 1960s or the "pencil-thin" eyebrows of the 1920s.

| Culture / Era | Aesthetic Ideal | Common Practices | Symbolic Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modern Western | Minimalist, symmetrical, "tucked" look with little to no visible labia minora. | Total depilation (waxing/laser), Labiaplasty. | Youthfulness, hygiene, and alignment with digital/media standards. |

| Khoisan (Southern Africa) | Elongated labia minora (the "macronymphia"). | Manual stretching and pulling from a young age. | Maturity, sexual desirability, and cultural identity. |

| Ancient Greco-Roman | Smooth, hairless skin; natural anatomical proportions. | Use of tweezers, resins, and pumice stones for grooming. | Civilization over "wildness," discipline, and high social status. |

| Traditional East Asian | Light pigmentation and high contrast between skin and tissue. | Use of natural brightening agents; preservation of some pubic hair. | Vitality, purity, and "primness." |

| Renaissance Europe | Soft, rounded forms; largely natural and un-manicured. | Minimal intervention; focus on overall body fullness. | Fertility, health, and the abundance of nature. |

Toward a Modern Traditional Acceptance

So, where does this leave the modern woman? We live in an era where we are bombarded with images of a single, narrow standard of beauty, yet we are also the heirs to a vast history of cultural variation.

The path forward is one of honest, grounded acceptance. We can appreciate the modern desire for grooming and aesthetics without feeling the need to surgically alter our biological heritage to fit a passing trend. There is a quiet confidence in recognizing that our bodies are designed for more than just a visual "look"—they are designed for life, for intimacy, and for the continuation of the human story.

A modern traditional approach to body acceptance is not about rejecting beauty; it is about broadening our definition of it. It is about understanding that a woman's value is not measured by the millimeters of her labia or the color of her skin. It is about respecting the body as it is, recognizing that it is a functional, living thing, not a plasticized ideal.

Men and women both benefit when we move away from these unrealistic pressures. When women feel confident in their natural form, it fosters a more authentic and healthy relationship with themselves and their husbands. It allows for a focus on what truly matters: health, connection, and the celebration of the feminine spirit.

Finding Balance

In the end, the history of genital aesthetics tells us that there is no "wrong" way to be a woman. Whether we look at the stretched labia of the Khoisan, the groomed skin of the Romans, or the natural variations of the modern Western woman, we see a common thread: the female body is a vessel of incredible diversity and strength.

We should be wary of any trend that tells us our natural state is something to be "fixed." Instead, we can look at our bodies with the same appreciation we might give to a piece of classical architecture or a natural landscape—full of unique lines, unexpected curves, and a history that is entirely our own.

By understanding the cultural roots of these beauty standards, we can strip away the anxiety they often produce. We can choose to groom because it makes us feel good, or we can choose to leave ourselves as nature intended, knowing that both choices are valid. The true "ideal" is a woman who is at peace with her body, standing firm in the knowledge that she is a masterpiece of biological design, regardless of the era’s fleeting fashions.

Common Questions

Is there a medically "perfect" size or shape?

No. Medical professionals recognize a vast range of sizes, shapes, and colors as perfectly healthy. Variation is the biological norm for women.

Why is symmetry so emphasized in modern media?

Symmetry is often equated with health in general evolutionary psychology, but its application to intimate anatomy is largely a result of digital airbrushing and the rise of specific photographic trends.

Is hair removal a new historical trend?

No. As seen in Ancient Roman and Egyptian records, grooming has been practiced for millennia, though the "ideal" amount of hair has fluctuated significantly by culture.

A Note on Moving Forward

The conversation about our bodies doesn't have to be one of shame or clinical coldness. It can be a conversation of grace and reality. As we navigate the pressures of the modern world, let us hold onto the fact that our bodies are the result of thousands of years of successful evolution. Every curve, every fold, and every variation is a testament to the resilience of the women who came before us.

The Takeaway

What this comparison reveals is that women’s bodies have never been "standardized." Every era selects a specific trait—whether it is the length of the labia, the presence of hair, or the shade of the skin—and holds it up as the pinnacle of beauty.

By observing these shifts, we can see that the current Western trend toward surgical "perfection" is just one chapter in a much longer book. Embracing a Modern Traditional view means honoring your individual biology while choosing grooming habits that make you feel confident, rather than conforming to a rigid, temporary ideal.

Mindful Tools

- ✨ Perspective: Remind yourself that symmetry is a media trend, not a biological requirement.

- 📖 Education: View anatomical diagrams to see the vast range of "normal."

- 🧴 Gentle Care: Use pH-balanced, fragrance-free cleansers only on external skin.

The Essentials

| DO: | Wear breathable cotton fabrics. |

| DO: | Consult a professional if you feel physical discomfort. |

| DON'T: | Compare your unique body to airbrushed images. |

| DON'T: | Use harsh chemicals or whitening agents. |

"Confidence is the most enduring aesthetic. Honor the body you were given."

Disclaimer: The articles and information provided by the Vagina Institute are for informational and educational purposes only. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or another qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition.

Deutsch

Deutsch  English

English  Español

Español  Français

Français