The Warp of Time and the Weft of Grace: Finding My Rhythm in Willow

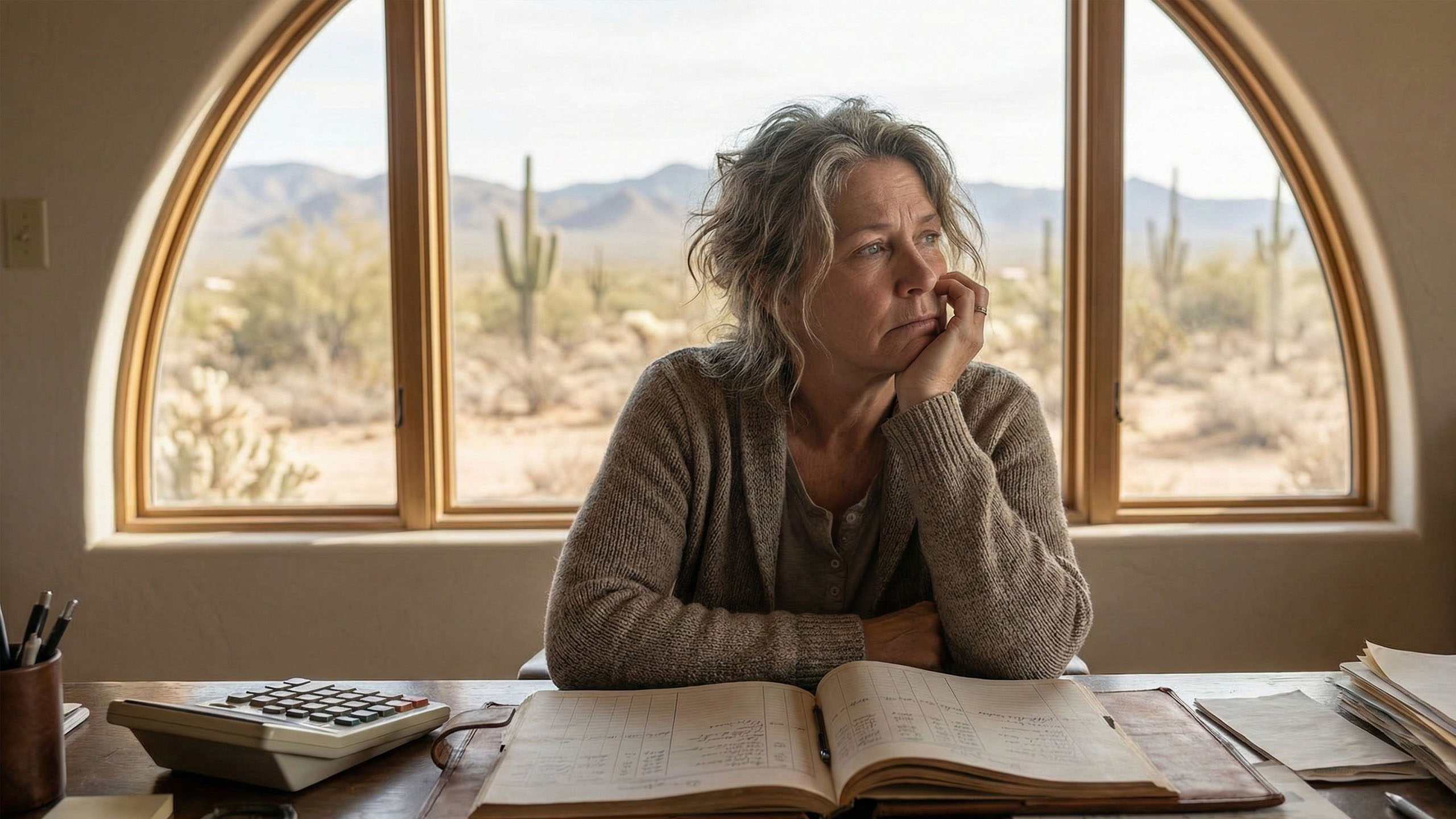

There is a specific kind of silence that settles into a home once the children have grown and the frantic pace of mid-life begins to steady. It is not an empty silence, but rather a reflective one—a quiet that asks, “And what shall we do now?” For years, my identity was defined by the roles I filled for others. I was a wife, a mother, a daughter, and a professional.

My hands were always busy, but they were busy with the ephemeral: typing emails that would be deleted, folding laundry that would be unfolded, and preparing meals that would be consumed in twenty minutes. I longed for something tangible. I wanted to create something that would outlast the afternoon, something that required a different kind of patience than the kind used while waiting for a teenager to come home past curfew.

I found that something in the unlikely form of a bundle of damp, smelling-of-the-earth willow rods.

At fifty-five, I decided to learn the ancient art of basket weaving. It wasn’t a choice born of a sudden whim, but rather a return to a more traditional way of being. I wanted to step away from the digital hum and the constant stream of information that defines our modern existence. I wanted to see if I could still learn, if my hands could still be taught new tricks, and if I could find a sense of quiet mastery in a craft that women have practiced since the beginning of recorded history.

The Humble Beginning of a Weaver

My first class was held in a drafty community center on a Saturday morning in November. I walked in, feeling a bit out of place with my neatly manicured nails and my leather handbag, surrounded by women who looked like they knew their way around a garden spade. Our instructor, a woman named Martha who had been weaving for forty years, looked at us over her spectacles and said, “The first thing you must learn is that the wood is in charge. You are simply there to suggest a direction.”

That was my first lesson in humility. In my professional life, I was used to being in charge. In my home, I was the coordinator of chaos. But as I sat down with my first set of "staves"—the thick, upright ribs that form the skeleton of a basket—I realized that my will mattered very little if I didn't respect the tension of the material.

The process of weaving is deceptively simple: you have the warp (the vertical staves) and the weft (the horizontal weavers). You go over one, under one. Over, under. It sounds like a child’s game, but the physical reality is a different story.

My fingers, more accustomed to a keyboard than a woody vine, felt clumsy. By the end of the first hour, my thumbs were aching. By the second hour, I had a blister forming on my index finger. My basket—if you could call it that—looked like a lopsided bird’s nest that had survived a Category 5 hurricane.

“Don’t fight the willow, Sylvia,” Martha said, pausing at my station. “If you force it, it will snap. You have to soak it until it’s supple, and then you have to guide it firmly but gently. It’s like raising a child; if you’re too rigid, they break. If you’re too loose, there’s no structure.”

I looked at my warped, wobbly creation and laughed. It was a mess. But for the first time in years, I wasn't worried about being perfect. I was simply focused on the next "under."

The Physicality of the Craft

There is something deeply grounding about working with natural materials. In our modern world, we are surrounded by plastic, glass, and cold metal. To spend an afternoon with willow, seagrass, or ash is to reconnect with the physical world in a way that feels almost medicinal.

The preparation alone is a ritual of patience. You cannot simply decide to weave a basket and begin. The material must be prepared. Dried willow must be soaked in water—sometimes for days—to regain its flexibility. You have to plan. You have to wait. This flies in the face of our "instant gratification" culture, where we expect everything to be available at the click of a button.

As the weeks went by, I noticed a change in myself. My hands grew stronger. The skin on my palms toughened. I began to appreciate the subtle differences in the materials. Willow is stubborn and sturdy; it makes for a basket that can carry a heavy load of firewood or apples. Reed is more forgiving, allowing for intricate patterns and delicate shapes.

I also began to appreciate the "Modern Traditional" lifestyle. It isn’t about rejecting progress or moving to a cabin in the woods. It’s about bringing the values of the past—durability, hand-craftsmanship, and patience—into our contemporary lives. When I carry my hand-woven basket to the local farmers' market, I feel a sense of pride that no designer handbag could ever provide. That basket represents hours of focused labor. It represents the fact that I didn't give up when the base was uneven or the rim wouldn't close.

A Community of Hands

One of the most unexpected joys of learning this new skill was the community I found. In our class, there were women from all walks of life. There were younger women looking for a creative outlet, and women my age who were navigating the quiet transitions of later life.

We didn't talk about politics, and we didn't spend time on the latest social media controversies. Instead, we talked about our gardens, our husbands, our grandchildren, and the best way to finish a "rolled border." There is a unique bond that forms between women when they are working with their hands. The shared focus on a task allows for a different kind of conversation—one that is steady, honest, and unhurried.

In these circles, I saw the beauty of traditional roles and the strength of femininity. We weren't trying to "break glass ceilings" in that room; we were trying to build something that would hold the weight of a harvest. There was a profound respect for the wisdom of the older women, the "master weavers" who could fix a mistake with a flick of their wrist that would have taken me an hour to unpick.

I realized that learning a new skill later in life isn't just about the skill itself. It’s about placing yourself in the position of a student again. It’s about acknowledging that you don't know everything and that there is immense value in the experience of those who came before you.

The Philosophy of the Vessel

As I became more proficient, I started thinking about the symbolism of the basket. A basket is a vessel. Its entire purpose is to hold, to carry, and to protect.

In many ways, this is the story of a woman’s life. We spend so much of our time being the vessels for our families. We hold their worries, we carry their schedules, and we protect their dreams. But a basket can only hold things if it is structurally sound. If the "warp" is weak, the whole thing collapses.

Learning to weave taught me that I need to maintain my own structure. If I don't take the time to "soak"—to replenish my own spirit and learn new things—I become brittle. And a brittle weaver cannot create anything of lasting value.

I remember one particular afternoon when I was working on a large garden trug. It was a complex project, requiring a heavy wooden handle and a specific "rib" construction. I was struggling with the tension, and I felt that old familiar flash of frustration. I wanted to be good at this now. I wanted the finished product without the messy middle.

I took a breath and looked at my hands. They were stained a light brown from the tannin in the willow. They looked like my mother’s hands. I realized then that the "messy middle" is where the actual life happens. The finished basket is just the evidence of the time spent. The real value was in the two hours of silence, the rhythmic motion of the wood, and the steady breath I was finally learning to take.

The Value of the "Hard Way"

We live in a time that prizes efficiency above almost everything else. We are told that "easier is better" and "faster is smarter." But basket weaving is inherently inefficient. You can buy a plastic bin at a big-box store for five dollars that will hold just as much as my willow basket.

So why do it?

We do it because the "hard way" builds character in a way the easy way never can. When you spend twenty hours making a single object, you develop a relationship with that object. You know every flaw. You know the spot where the reed nearly snapped and you had to carefully splice in a new piece. You know the strength of the base because you were the one who tightened the slath.

This perspective has bled into other areas of my life. I find myself more willing to take the long route in conversations with my husband. I am more patient with the slow growth of the perennials in my garden. I am less inclined to look for the "quick fix" for complex problems.

Learning a new skill at this stage of life has been an affirmation of my own agency. It is a reminder that while our roles change—as children grow and careers wind down—our capacity for growth does not have to. A woman in her fifties, sixties, or seventies is not a finished product. She is a work in progress, much like the basket on my workbench.

Passing the Torch

Recently, my granddaughter, Chloe, came to visit. She’s seven, an age of endless curiosity and high energy. She saw me working on a small berry basket in the sunroom and stopped, mesmerized.

“Can I try, Grandma?” she asked.

I looked at her small, soft hands and then at the tough willow. I knew it would be hard for her. I knew she would get frustrated. But I also knew she needed to feel the resistance of the wood.

I sat her on my lap and we worked together. Over, under. Over, under. I showed her how to use her thumb to hold the tension. I watched her face screw up in concentration, and I saw the light of discovery in her eyes when she completed her first full row.

In that moment, I felt a profound sense of continuity. I wasn't just teaching her how to make a container; I was passing down a tradition. I was showing her that a woman’s hands are capable of building things, of fixing things, and of creating beauty out of the raw materials of the earth.

Men and women have distinct ways of interacting with the world, and there is a specific, quiet strength in the way women have historically managed the domestic sphere. By teaching Chloe to weave, I was connecting her to a long line of women who knew how to provide for their homes with grace and skill.

The Finished Piece

Today, my home is filled with baskets. There is a large one by the fireplace for logs, a shallow one on the dining table for fruit, and several small ones in the guest room for soaps and linens. They aren't perfect. If you look closely, you can see where my tension was a bit tight or where a rim is slightly asymmetrical.

But to me, they are beautiful. They represent a journey of rediscovery. They represent the fact that I chose to be a beginner again, to endure the blisters and the frustration, and to come out the other side with something real.

For any woman who feels the stirrings of restlessness, who feels that the quiet of an empty nest is a bit too loud, I encourage you to find your own "willow." It doesn't have to be basketry. It could be woodworking, or quilting, or restoring old furniture. The specific craft matters less than the act of doing.

Find something that requires your full attention. Find something that cannot be rushed. Find something that connects you to the physical world and the traditions of those who came before you.

We are often told that the later years of a woman's life are a time of "fading." I have found the opposite to be true. It is a time of hardening—not in the sense of becoming cold, but in the sense of becoming durable. Like a well-woven basket, we become stronger through the intersections of our experiences. We become capable of carrying more, of holding more, and of lasting longer.

As I sit here now, with a fresh bundle of willow soaking in the tub, I don't see a chore ahead of me. I see an opportunity. I see a chance to sit in the sun, to feel the wood beneath my fingers, and to continue the slow, beautiful work of weaving a life that is sturdy, useful, and entirely my own.

The silence of the house is no longer a question. It is an invitation. And I am happy to answer it, one "over and under" at a time.

By Sylvia M.

Deutsch

Deutsch  English

English  Español

Español  Français

Français